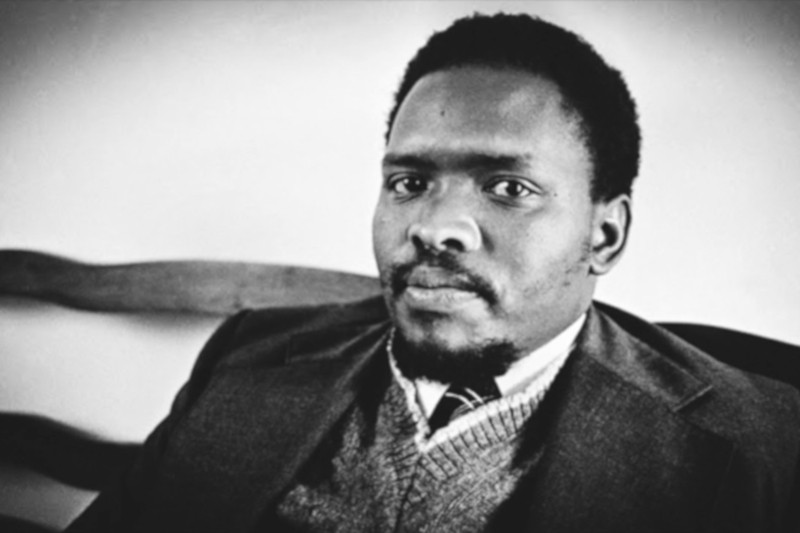

September 12 this year marks the 38th anniversary of the assassination of Steve Biko, the historic liberation fighter who sacrificed his life so that future generations of South Africans would be liberated to live in a society where race was no longer a point of reference and where Blackness was seen as a positive symbol of culture and identity, as opposed to the erstwhile imposition of whiteness as normative and the aberration of Blackness in apartheid South Africa. Biko adamantly opposed the culture of capitalist exploitation as pathological and excoriated the rampant individualism of capitalism. For African societies, Biko admonished, the collective was paramount and individual well-being was always situated within the context of community welfare. Biko himself embodied the ethic of community sharing and generosity, collectively initiating effective organizations that worked for the mental and physical health of the Black poor via organizations like the Black People’s Convention, Black Community Programs, Zimele Trust Fund, and Impilo Community Health Clinic at Zinyoka outside King Williams Town.

Sadly, even tragically for South Africa, Africa, and so much of the world, the lessons from the life and life-sacrifice of Steve Biko continue to go unheeded. Biko lamented then and he certainly would now, that Black people were vying for entry into an exploitative capitalist system “in which the poor grow poorer and the rich richer in a country where the poor have always been Black.” The sprinkling of a few Black billionaires and millionaires amid the sea of majority privileged and economically secure whites in South Africa and where just 5% of Black students receive university degrees today, was precisely what Biko denounced almost 40 years ago because he viscerally understood that a colonial system, like its successor, capitalism, was by its nature exploitative, extractive, unjust, and benefitting a tiny minority since it was based on the accumulation of monetary and material wealth at the cost of the impoverishment of the vast dispossessed majority. In Biko’s understanding, human life was immeasurable in monetary worth and infinitely priceless—ubuntu. Money is fluid in its value, as South Africa and the world realized a couple of weeks ago, when $3 trillion was erased in global stock markets. Thousands of people were laid off as a result of fluctuating mining and other stock indices. People were and are sacrificed for money in a capitalist system. Money has taken on deification status and is now entrenched as the principal arbiter of human and other life value. Many people are brainwashed into sacrificing their lives for expendable materialistic things so much so that they would rather hold onto their cellphones rather than giving it up to a gun-toting robber to save their lives (this is by no means defending the criminal act of robbery, but simply to reinforce the point).

Essentially, Biko was fully aware of the social crisis that would envelop South African society with embracement of capitalist individualism and the accompanying sense of rootless and ruthlessness, in which Black people would increasingly become siphoned into a system that minimizes the sense of Indigenous African cultural roots where collective well-being was foundational and opt for integrating into a system led by people from corporate “Coca-cola hamburger cultural backgrounds.” Biko anticipated the progressive breakdown of the traditional extended family unit of African culture, inevitable in a system where accumulation of money was sacred and people would be sacrificed for this principle. He knew that generation gaps between elders and the youth would widen as youth were indoctrinated by a “Western” educational system that generally shunned Indigenous cultural traditions and where parents, grandparents, and elders were considered devoid of wisdom and knowledge, inevitably losing their roles of parental authority and being replaced by teachers of “Western” educational values. Biko saw that family units that were once intimately interwoven with each other would begin to gradually diminish and disintegrate under economic pressures that forced millions to migrate to toil in the mines or seek employment hundreds of kilometers away from home. This is the ugly lot of exploitative and insouciant capitalism that Biko recognized and warned against and that is now cardinal in contemporary South African political economy.

Most importantly, Steve Biko epitomized a human being who understood his purpose in life: to use the gift of life to enhance the lives of those who were deprived and oppressed. His life was purposeful and his passing was never in vain: the ancestors of freedom fighters in Africa warmly embrace him. Today, that sense of purpose for all youth living in technologically-driven, money-oriented, and materialistic-aspiring cultures in the world is fast eroding as billions of youth succumb to the mad rat-race of being successful by getting to the top of the ladder in a dog-eat-dog world. Resultantly, the poor are left to their lot of entrenched misery as if such is divinely ordained. All must reclaim the purposefulness of Steve Biko’s life, so that the world can, in Biko’s words, adorn a “more human face.

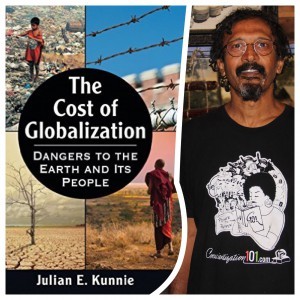

Julian E. Kunnie is a professor of religious, Latin American, Middle Eastern and North African studies at the University of Arizona. His articles have appeared in the African Studies Review, the Black Scholar, the Journal of African American History, the Journal of the African American Academy of Religion, the Journal of Pan African Studies, and other noted journals and publications such as ours. Checkout the interview we conducted with him on our podcast regarding his critically acclaimed book Is Apartheid Really Dead?: Pan-Africanist Working-Class Cultural Critical Perspectives. His latest book is The Cost of Globalization: Dangers to the Earth and Its People (McFarland, 2015). On Saturday September 12, 2015, the 38th anniversary of the assassination of Steve Biko, Julian will be doing a book-signing at Barnes & Noble in Tucson, AZ from 2-5pm for his new book, and will honor Steve Biko as well. The location’s address is 5130 E. Broadway Blvd.

Julian E. Kunnie is a professor of religious, Latin American, Middle Eastern and North African studies at the University of Arizona. His articles have appeared in the African Studies Review, the Black Scholar, the Journal of African American History, the Journal of the African American Academy of Religion, the Journal of Pan African Studies, and other noted journals and publications such as ours. Checkout the interview we conducted with him on our podcast regarding his critically acclaimed book Is Apartheid Really Dead?: Pan-Africanist Working-Class Cultural Critical Perspectives. His latest book is The Cost of Globalization: Dangers to the Earth and Its People (McFarland, 2015). On Saturday September 12, 2015, the 38th anniversary of the assassination of Steve Biko, Julian will be doing a book-signing at Barnes & Noble in Tucson, AZ from 2-5pm for his new book, and will honor Steve Biko as well. The location’s address is 5130 E. Broadway Blvd.