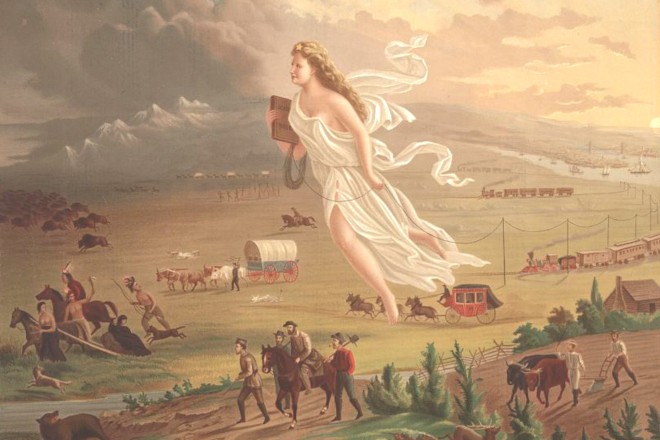

Nate Parker’s movie The Birth of a Nation has revived the question: What caused Nat Turner’s 1831 uprising? Turner, first of all, was not a deranged misfit who acted outside of a historical context of previous African freedom fighters. Throughout slavery’s duration, resistance was not only constant and fatal, but twofold . . . Africans equally resisted both slavery and Americanization.

Contrary to popular “feel good” versions of history, the “fight against slavery” should not be presumed as a “fight to become American.” For enslaved Africans like Turner, Americanization was the obstacle – not the vehicle – to the freedom they sought.

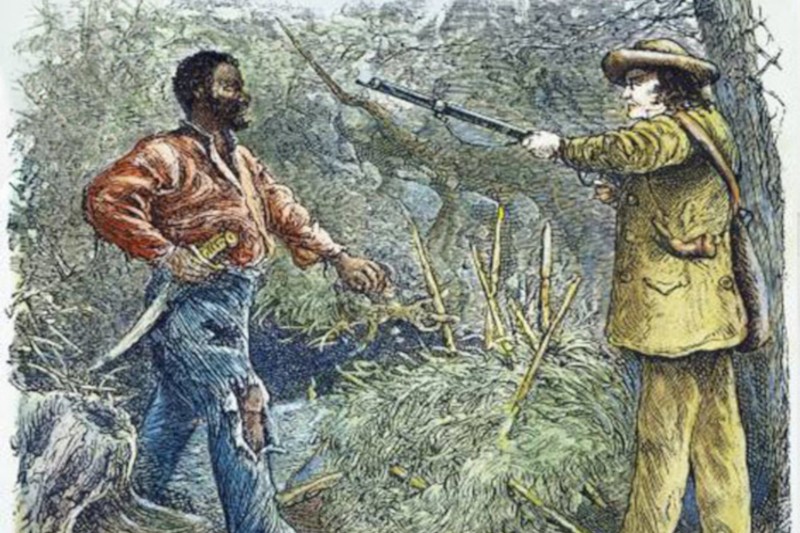

A largely overlooked factor that forged Africans into Americans was their inability to muster enough weapons to militarily free themselves from Americanization. Along with the 2nd Amendment which allowed Whites to bear arms, slavery was also backed by America’s military, which is why 800 soldiers deployed against Turner. Within this context of warfare (which fomented at least 313 recorded armed uprisings), there is provable evidence that Africans became Americans – not by virtue of winning the Civil War – but by virtue of prior military defeats.

CNN Town Halls won’t discuss this, but numerous captives were already soldiers in Africa beforehand, who like Turner, held deep monotheistic beliefs. Once in America these battle-tested troops launched guerilla forms of warfare whenever possible, using whatever weapons possible, with clear theological convictions that fused spirituality with revolution. Naturally, after being forcibly uprooted 5,000 miles from long-lived kingdoms and cultures, they deemed Euro-Americans as new adversaries, and Americanization was certainly not their goal.

This explains why tens of thousands of Africans militarily fought with the British against America during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Plus, another 100,000 fled or died fleeing to join British forces. Conclusive stats are unknown, but from a sheer combat perspective, the Revolutionary War could be framed as the largest uprising of Africans who ever unified to militarily free themselves from Americanization . . . including Africans reportedly owned by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Despite being defeated, it is still necessary to credit legitimacy to such Africans, beyond distorted narratives that label Turner an “African American” even though men like him sought America’s military downfall. Olaudah Equiano (an Ibo, captured at age 11, who published the first surviving “slave account” in 1789: The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano) wrote, “When you make men slaves, you compel them to live with you in a State of War.” Once freed in 1792, he bolted like lightning to England.

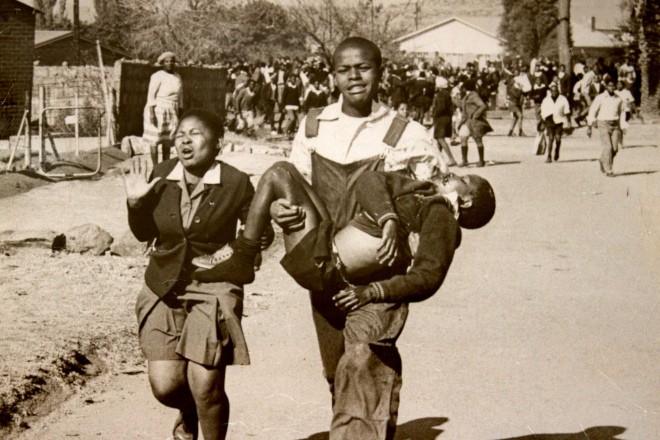

Haiti’s independence (1804) ignited further military motivations. On July 4th, 1804, instead of recognizing US independence, hundreds of Blacks in Philadelphia stormed Independence Hall to live Haitian independence vicariously. Flanked in military formations, they carried swords and attacked Whites for two days, chanting “we will show them [Whites] St. Domingo [bloodshed like Haiti].”

So, by the dawn of his 1831 uprising, Turner was just one cog in a long continuum of such idealists. Other notable military operations involved: Fort Mose in Florida (1738-1763); the Stono Uprising in South Carolina (1739); the German Coast Uprising in Louisiana (1811); Negro Fort in Florida (1815); and David Walker’s Appeal (1828) advocated revolution and religion (even though Walker was more an assimilationist than sovereignist).

Men like Turner also equated themselves to other hemispheric freedom fighters (in nations like Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Columbia) who gained independence . . . including Euro-Americans. For example, before being hanged for their 1800 planned uprising, one of Gabriel Prosser’s soldiers retorted, “I have nothing more to offer than what General [George] Washington would have had to offer, had he been taken by the British and put to trial. I have adventured my life in endeavouring to obtain the liberty of my countrymen, and am a willing sacrifice in their cause.” Translation, he meant, “Bring It: I stand upon universal principles of freedom that – just like you – I will never compromise.”

Interestingly, in a 60 Minutes interview, Nate Parker paralleled Nat Turner to George Washington in terms of their shared idealisms to “Birth a Nation.” From this perspective, whether you agree or disagree with Turner’s guerilla tactics, his comparative cause to end tyranny was no less honorable than America’s founders.

Tyranny however can be a very peculiar and subjective creature, since “one man’s tyranny can be another man’s liberty.” Hence, George Washington, who enslaved and tyrannized over 300 Africans is deified on Mt. Rushmore as a hero, while conversely, Nat Turner who fought against slavery’s tyranny is demonized as a savage. To this contradiction, James Baldwin once quipped, “In the US, violence and heroism have been made synonymous . . . except when it comes to Blacks.”

This article was culled in part from The Sovereign Psyche: Systems of Chattel Freedom vs. Self-Authentic Freedom by Ezrah Aharone who is an adjunct associate professor of political science at Delaware State University. He is also a political and business consultant on African affairs, as well as the author of Sovereign Evolution and Pawned Sovereignty.

This article was culled in part from The Sovereign Psyche: Systems of Chattel Freedom vs. Self-Authentic Freedom by Ezrah Aharone who is an adjunct associate professor of political science at Delaware State University. He is also a political and business consultant on African affairs, as well as the author of Sovereign Evolution and Pawned Sovereignty.