ABSTRACT: This is a brief study guide designed to engage viewing audiences of Haile Gerima’s film Teza in a critical analysis inspired by some of the classical critical insights put forth by Frantz Fanon. It is comprised of ten questions which encourage viewers to move beyond the entertainment value of the film, of necessity, to reflect on its socio-political significance with regard to African people throughout the world. All of Gerima’s work consistently depicts the lives of Black people from a Pan-African perspective. Teza could perhaps be his magnum opus. It is committed to sharpening African people’s consciousness and cultivating the desire to build a new social order, worldwide. Fanon’s own work expressed revolutionary insights on the conditions of colonized and racialized, African and “Third World” subjects at large. Gerima continues this tradition by depicting Fanon’s insights cinematically. Moreover, not only does Gerima subvert the juggernaut film establishment by distributing his and other films, independently, he does so as well by taking his films directly to those communities he represents for exhibition and collective discussion. Therefore, this brief study guide can be used as a critical tool that upholds Fanon’s revolutionary, anti-colonialist insights and fosters in-depth discussions of Gerima’s cinema particularly among those Global African communities affected by colonialism, neo-colonialism or imperialism today.

INTRODUCTION:

The political party in many parts of Africa which are today independent is puffed up in a most dangerous way. In the presence of a member of the party, the people are silent, behave like a flock of sheep, and publish panegyrics in praise of the government or the leader. But in the street when evening comes, away from the village, in the cafés or by the river, the bitter disappointment of the people, their despair but also their unceasing anger makes itself heard. The party, instead of welcoming the expression of popular discontent, instead of taking for its fundamental purpose the free flow of ideas from the people up to the government, forms a screen, and forbids such ideas. The party leaders behave like common sergeant-majors, frequently reminding the people of the need for “silence in the ranks.” This party which used to claim that it worked for the full expression of the people’s will, as soon as the colonial power puts the country into its control hastens to send the people back to their caves.

– Frantz Fanon[1]Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press 1963) 182-183.

Haile Gerima not only deconstructs the notion of European universality, in Teza, he also shows the tragedy and barbarism of grafting a socio-economic ideology onto African people and African situations while ignoring the unique socio-economic needs of African people. It would be all too easy to make a film that merely lambasts capitalism in a rather banal fashion. With a fearless critique of socialist imperialism, or socialist colonization, what unfolds in Teza is actually, literally a phenomenological representation of Frantz Fanon’s writing in The Wretched of The Earth, especially “The Pitfalls of National Consciousness,” one of its most stunning chapters. Cinematically, Gerima reveals these pitfalls in a raw and stinging critique of the false universalism of Western socialism or its application in Africa via officially Marxist-Leninist political states and political parties; and this critique stings like the application of a “perm” or a “conk” on an African head. Hence, critically, Teza can only be seen as an indictment of all socialism as such if one, colonizer or colonized, views socialism as only being “authentic” as it was interpreted by European thinkers, such as Marx, Engels and Lenin, of course.

Briefly, let us put a finer point on what Gerima does is a brilliant film. In Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s War, Patrick Chabal writes:

Cabral’s analysis shows that he was not concerned with a theoretical discussion of Marxism per se but with its relevance to colonized societies. His historical specificity and his uncompromisingly African perspective were implicit criticisms of much orthodox European Marxism of the time. ‘Marxism is not a religion,’ he once said, and Marx did not write about Africa.[2]Patrick Chabal, Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s War (Trenton: Africa World Press, 2003), 170.

There was no period in history called “The Renaissance,” but there was a period in human history called “The European Renaissance.” To efface the “European” in “Renaissance” is to place Europe at the center of humanity. This same mistake can be made in terms of revolutionary political ideologies as well as historical or historiographical ideologies, indeed, all academic-intellectual ideologies. They may sound sweet and egalitarian, but they are doomed to fail if they have this gargantuan blind spot. Thus, Kwame Nkrumah himself wrote in Consciencism:

It is not only the study of philosophy which can become perverted. The study of history too can become warped. The colonized African student, whose roots in his own society are systematically starved of sustenance, is introduced to Greek and Roman history, the cradle history of modern Europe, and he is encouraged to treat this portion of the story of man together with the subsequent history of Europe as the only worthwhile portion. This history is anointed with a universalist flavouring which titillates the palate of certain African intellectuals so agreeably that they become alienated from their own immediate society.[3] Kwame Nkrumah, Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonization (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1964), 5.

The protagonist of Teza is the aforementioned African student, and he goes by the name of Anberber.

CRITICAL SYNOPSIS:

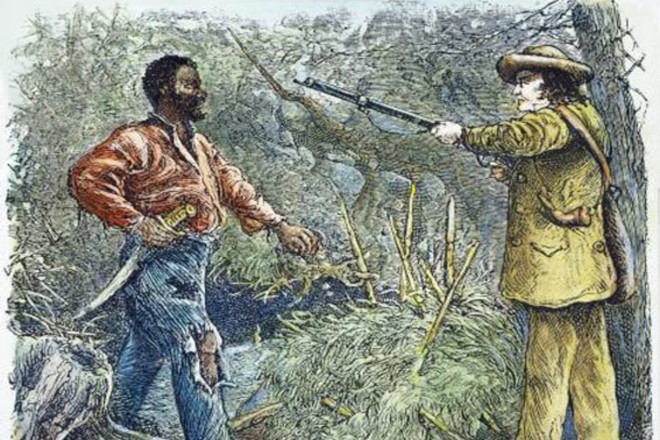

When we are first introduced to Anberber he is wrapped up like mummified Akhenaton in a Western hospital setting; we have no idea what has happened to him, but Gerima instantly stimulates our interest. When we first see Anberber outside of his bandages and in his homeland of Ethiopia, he is an older man who has clearly been mentally and physically mutilated. Still, not only is his mother ecstatic upon his return, but his whole village is overjoyed. It is revealed that Anberber left home to pursue education in East Germany; he is a doctor. He is also not just another “smart” African chosen to go be “educated” in the West: Anberber comes from very respected family in his village, as his father was a heroic African patriot, one who was killed with poisonous gas by Italian fascists at “The Battle of Tekazi River.” In their village there is a monument called “Mussolini Mountain,” Anberber’s “childhood playground,” which was built to commemorate African patriots who were killed defending their homeland from Italian colonialism.

Once at home, Anberber lives in an extreme malaise, an almost comatose state. He is essentially alienated but not in the Marxist sense of alienation from the fruits of one’s labor. He is alienated from his own humanity as a colonized and traumatized being. Existentially, he cannot make sense of his life of turmoil in the least, and it is his total lack of understanding, despite his many years of Western schooling, that Gerima lays out before us. If it was merely an issue of Marxist alienation, we might not need a movie here at all: Anberber could have just taken over a factory. But his homecoming serves to further alienate himself from his village, which he thought would be a refuge and source of relief. He soon learns that his country is in the midst of a “civil war,” or a violent fight between the military regime and its political opponents to determine who are the “true socialists.” He learns that adolescent boys are routinely taken by force to fight in this ravaging war. He also learns that many young boys now hide out in caves to avoid conscription or military kidnapping. What’s more, Anberber is suffering from puzzling nightmares and hallucinations, wondering aloud as to what could possibly cure his personal and village ails.

How can we relate this to Fanon, a figure widely known to be central to Haile Gerima’s historic work on film?

10 STUDY QUESTIONS:

1. The main character of Teza, Anberber may be a clear embodiment of the “honest intellectual” that Frantz Fanon describes as follows:

In those underdeveloped countries which accede to independence, there almost always exists a small number of honest intellectuals, who have no very precise ideas about politics, but who instinctively distrust the race for positions and pensions which is symptomatic of the early days of independence in colonized countries. The personal situation of these men (breadwinners of large families) or their background (hard struggles and a strictly moral upbringing) explains their manifest contempt for profiteers and schemers. We must know how to use these men in the decisive battle that we mean to engage upon which will lead to a healthier outlook for the nation.[4]Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 177.

How were Anberber’s skills and commitment to improving the conditions of the people of Ethiopia abused under “the Derg,” or the military regime that took over after the fall of Haile Selaissie’s rule? How did this use and abuse undermine a “healthier outlook” for the nation, according to Fanon’s descriptive analysis in “The Pitfalls of National Consciousness” chapter of The Wretched of the Earth?

2. Throughout Teza, we see pictures of Mengistu Haile Mariam, President of the “People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia” from 1987 to 1991, writ large in several scenes. With these images, is not Gerima illustrating Fanon’s observation that “bourgeois” dictatorships in underdeveloped countries control the masses through the “moral” power of the leader, which is in stark contrast to the economic power of the bourgeoisie in imperial, industrialized societies?[5] Ibid., 165-166. Since there is no economic independence, development or a coherent economic plan, the bourgeois dictatorship uses brute force and mysticism as their only forms of “currency” to secure power and personal gain. What are some examples of how this dynamic is manifest throughout the film?

3. Fanon also writes:

To educate the masses politically does not mean, cannot mean, making a political speech. What it means is to try, relentlessly and passionately, to teach the masses that everything depends on them; that if we stagnate it is their responsibility, and that if we go forward it is due to them too, that there is no such thing as a demiurge, that there is no famous man who will take the responsibility for everything, but that the demiurge is the people themselves and the magic hands are finally only the hands of the people.[6] Ibid., 197

How much do Anberber or his medical student comrades understand this mandate? How would such an understanding lead to an evitable conflict with the forces of repression on display in Teza? How does Anberber’s understanding of education and the masses change or shift by the end of the film?

4. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire, who uses Fanonian frameworks himself, introduces the “banking” concept of education. This is the traditional teaching style where education becomes an act of depositing information, wherein the students are the “depositories” and the teacher is the “depositor.” This pedagogy of oppression only permits students to receive or store the deposits of others, non-students. Freire then asserts that people who are denied the right to speak “their word” are situated in a “dehumanizing aggression.”[7]Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary Edition, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Inc., 2000), 72,88.

Discuss how the political “opposition” pictured in Teza perpetuated this “dehumanizing aggression” when they were supposedly “educating” the people at gun point, outside, in the rural village area, under a tree? Despite their posture of opposition, how were they asserting their own power to define and control without making any effort to dialogue with the people rather than “fill” them up with an alternate set of propaganda? Here, does the “opposition” not fail as well to “put itself to school with the people,”[8]Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 150. as Fanon pleaded?

5. The films of Haile Gerima are well known for presenting a very critical view of the common burdens faced by colonized women under colonial male dominance. In what ways does Teza face and highlight this theme and social condition itself, overall? If, that is, we “must guard against the feudal tradition which holds sacred the superiority of the masculine element over the feminine.”[9] Ibid., 202.

6. More precisely, with or without Fanon’s “Colonial War and Mental Disorders” chapter of The Wretched of the

Earth in mind, how does this all affect the psychological health of the female characters of this African film in particular? For example, what went into Cassandra’s decision to abort her pregnancy, when Anberber shows little interest in having a child? What was Azanu feeling when she was driven to madness and killed her baby because his father was marrying another woman? What mental contradictions are at work in Gabi’s inability to deal with her white racist country’s harmful effects on her and Tesfaye’s Black son, Teodross? What emotional and other hardships did Anberber’s mother endure in her efforts to care for both of her sons and their socially inflicted wounds? Finally, what about all of the unnamed mothers of the Ethiopian children abducted for war as the country was crippled as a whole?

7. Upon Anberber’s first return to Addis Ababa from Germany, he suffers an acute malaise which appears to be symbolized by a leaking bathroom faucet. It is nothing short of “maddening” in several distinct scenes before his exit from the capital city. If this is considered from a Fanonian perspective, could not “The Drip” there represent the “pitfalls of national consciousness,” or what Fanon literally called the “mésaventures of la conscience nationale.” If so, how is “The Drip” a possible gauge of Anberber’s conscience and consciousness in motion, not to mention his mental stability?

8. In the very famous chapter of A Dying Colonialism entitled “This is the Voice of Algeria,” Fanon analyzes the radio as an instrument of colonial oppression as well as a possible instrument for anti-colonial liberation, depending on the specific historical context of struggle. At an early point in this dynamic, he writes:

The messages broadcast by Radio-Alger are listened to solely by the representatives of power in Algeria, solely by the members of the dominant authority and seem magically to be avoided by the members of the “native” society.[10] Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism, trans. Haakon Chevalier (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1965), 73.

Later in the dynamic, the colonized clamor around the radio en masse for news of their revolution’s victories. In Teza, Anberber is shown listening to the radio at various points, conspicuously, during at least three different scenes, when he is back in the Ethiopian countryside. What exactly do these scenes convey – with the radio – about him and his village or their relationship to a globalizing Western culture? What do they say about state power here in continental Africa and the communications of the radio, or communications media in general, at this particular point in African historical time?

9. After an elder interprets his recurrent dream or nightmare for him, as a dream about his subconscious frustration with his formerly esteemed Western education, Anberber gains some clarity and a sense of purpose. He realizes that his schooling will not provide any grand solutions for the people of Ethiopia or the world as he has come to know it. “If you really wish your country to avoid regression, or at best halts and uncertainties,” Fanon writes in The Wretched of the Earth, “a rapid step must be taken from national consciousness to political and social consciousness.”[11]Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 203. How does Anberber make this move or shift in consciousness, after he stops looking to Europe or the West as the model for the solution to African problems?[12] Ibid., 315-316 How, in the end, may the birth of his and Azanu’s baby to be raised in the cave where children escape political repression symbolize a new world of African political and social consciousness to come?

10. In closing, Gerima dedicates Teza to “all the Black people who have been beaten and killed just for being Black,” in addition to his mother and sister as well as countless Ethiopian youth who were killed for daring to bring sincere change in Ethiopia.” Is he suggesting that we all suffer the same global-historical regime of violence as Black people and thus share the same destiny, regardless of the local-national borders in which so many of us are still held captive?

ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

C-101 Editors were solicited to contribute to the Spring 2013 publication of the academic journal Black Camera Volume 4, addressing Haile Gerima’s 2008 film Teza. We decided our piece in the journal would be a study guide so people who viewed the movie could use these questions to critically think about the themes, events, and characters throughout the film. After a lot of voluntary hard work and editing, we completed the piece for the publication December 2012 and never heard from the editor and publishers again. The piece was published in Black Camera in April 2013 and it was not until March 2014, through our own research, that we found out this piece had been published. This was very disappointing because we agreed to participate in this project due to our high regard for Haile Gerima’s films and an understanding that his work deserves in-depth analysis. Unfortunately, there are editors/publishers who claim to be “anti-colonial”, “anti-capitalist”, “pro-Black revolutionaries” but they operate on a exploitative model by extracting value from writers, journalists, and other cultural workers to benefit their own careers and/or catalogs. They barely issue the writers any credit and cease communication once they are able to benefit from the finished product.

We are writing this narrative to inform any of you who are independent that it is important that you stay vigilant and discerning when working with people who claim they are against exploitation. Make sure they are trustworthy individuals who do not heavily rely on corporate or any other institutional funding because that seriously compromises their integrity. Regardless of whether or not this piece was published by the great academic overlords in the sky we were going to post this study guide. In fact, we discovered it was published in the process of posting this article during our quality review! We did not want this valuable study guide to be lost in the dust bin of academic circles and originally participated in the project so the questions could be accessible to everyday, working people. Teza is a very conscious movie that should be discussed at length. We encourage you to purchase the movie below, watch it with the family, and discuss these questions.

References

| ↑1 | Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press 1963) 182-183. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Patrick Chabal, Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s War (Trenton: Africa World Press, 2003), 170. |

| ↑3 | Kwame Nkrumah, Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for De-Colonization (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1964), 5. |

| ↑4 | Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 177. |

| ↑5 | Ibid., 165-166. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., 197 |

| ↑7 | Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary Edition, trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Inc., 2000), 72,88. |

| ↑8 | Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 150. |

| ↑9 | Ibid., 202. |

| ↑10 | Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism, trans. Haakon Chevalier (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1965), 73. |

| ↑11 | Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 203. |

| ↑12 | Ibid., 315-316 |