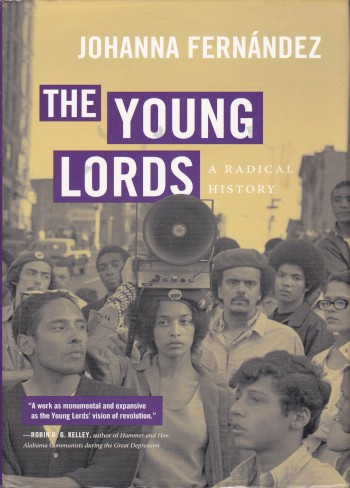

Against the backdrop of America’s escalating urban rebellions in the 1960s, an unexpected cohort of New York radicals unleashed a series of urban guerrilla actions against the city’s racist policies and contempt for the poor. Their dramatic flair, uncompromising socialist vision for a new society, skillful ability to link local problems to international crises, and uncompromising vision for a new society riveted the media, alarmed New York’s political class, and challenged nationwide perceptions of civil rights and black power protest. The group called itself the Young Lords.

Utilizing oral histories, archival records, and an enormous cache of police surveillance files released only after a decade-long Freedom of Information Law request and subsequent court battle, Johanna Fernández has written the definitive account of the Young Lords, from their roots as a Chicago street gang to their rise and fall as a political organization in New York. Led by poor and working-class Puerto Rican youth, and consciously fashioned after the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords occupied a hospital, blocked traffic with uncollected garbage, took over a church, tested children for lead poisoning, defended prisoners, fought the military police, and fed breakfast to poor children. Their imaginative, irreverent protests and media conscious tactics won reforms, popularized socialism in the United States and exposed U.S. mainland audiences to the country’s quiet imperial project in Puerto Rico. Fernández challenges what we think we know about the sixties. She shows that movement organizers were concerned with finding solutions to problems as pedestrian as garbage collection and the removal of lead paint from tenement walls; gentrification; lack of access to medical care; childcare for working mothers; and the warehousing of people who could not be employed in deindustrialized cities. The Young Lords’ politics and preoccupations, especially those concerning the rise of permanent unemployment foretold the end of the American Dream. In riveting style, Fernández demonstrates how the Young Lords redefined the character of protest, the color of politics, and the cadence of popular urban culture in the age of great dreams.

Another aspect of the book we thoroughly enjoyed was how Fernández explained the dynamics of race…i.e. anti-Africanity, within the Puerto Rican community, and how the Young Lords strove to abolish this contradiction. As Fernández wrote:

Although not inevitable, the rise of the Young Lords and their dynamic demographic composition reflected the social reorganization of postwar Puerto Rican life. Compared to the disproportionately white leaders of other Puerto Rican organizations, the Young Lords’ formal leadership body, the Central Committee, had a darker racial makeup. The majority, three out of five members, were Afro-Puerto Ricans. Two of the five, Juan González and David Perez, were fair-skinned Puerto Ricans who, absent their last names, might have passed for Italian American. The three others—Felipe Luciano, Pablo “Yoruba” Guzmán, and Juan “Fi” Ortiz—were unequivocally black. At first sight, their Afros, skin color, and facial features made them indistinguishable from black Americans. The same was true of the Young Lords’ membership. The racial profile of the leadership drew a disproportionate number of Afro-Puerto Ricans into the group’s ranks. Historically, many Afro-Puerto Ricans struggled to define themselves at the margins of two cultures with competing ideologies of race forged under very different social and historical conditions. They knew Puerto Rican antiblackness intimately. But they were also painfully familiar with their black American friends’ summary dismissal of Puerto Rican claims to language and ethnicity as fundamental markers of self-definition (242).

This book was a revelatory read, because it filled in the many intentionally created gaps about the totality of struggle waged against imperialism for self-determination in the late 1960’s to early 1970’s. GET YOUR COPY NOW!!! PALANTE!!!